PROBLEM STATEMENT

Totality was formed in 2021 to advance solutions to a problem 163 years in the making.[1]

The retirement of oil and natural gas wells involves pouring cement down a well’s casing to isolate subsurface formations that have been perforated to produce hydrocarbons. Once the casing has been cemented, hydrocarbons no longer are able to flow… In the case of inactive, orphaned or otherwise abandoned wells that are “shut-in” or “not producing”, sometimes hydrocarbons escape through leaks in valves and connections thus emitting hydrocarbons into the environment, whether onto the land in liquid form or into the atmosphere in gaseous state.

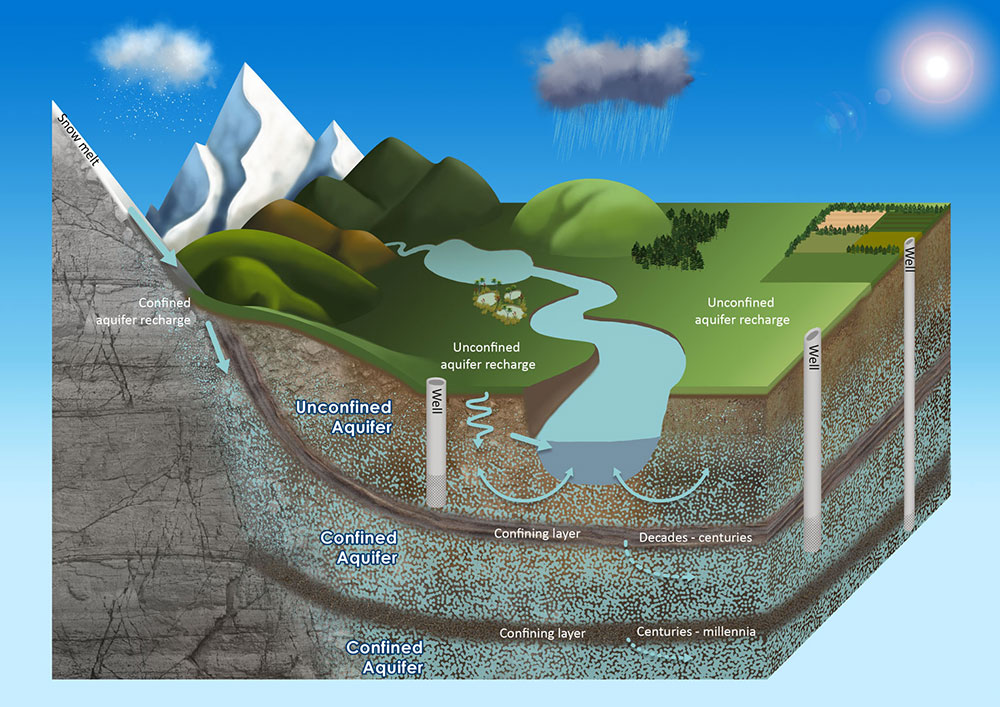

Protecting water-bearing aquifers (also called the "water table") from interference is of equal importance to retiring a wellbore.

"Plugging" wells is a risky business. Challenges are many, including handling workover rigs and associated equipment, unknown or unexpected pressure differentials between the surface and subsurface intervals, mechanical integrity of equipment, losing materials downhole, encountering casing integrity problems due to long-ago cement jobs, to name a few.

One cannot "abandon" a well until such retirement procedures are complete, and requisite notifications are submitted to the relevant Government Authority/ies.

Even still, usually a single well is among a field of wells. The conditions and parameters of a single well vary…some are capped with no remaining equipment. Or a natural gas well may still have a large "Christmas tree" with flowlines still connected. Or an oil well may still have a pumping unit, or nearby tank battery where oil was previously stored before turning to sales. Other wells are grown over with vegetation.

Further complicating matters, on private lands the surface estate is often owned by one party while the underlying mineral estate is owned by another. An oil & gas lease usually may comprise multiple wells, and generally requires asset retirement obligations be applied to the lease in its entirety.

The surface owner, who has provided surface use agreements, easements or otherwise, usually is an affected bystander as elder well and field infrastructure is an eyesore, but it is not always the surface estate owner’s authority to dictate solutions. A party seeking to plug a single well certainly is not wishing to inherent the entirety of the oil & gas lease retirement liabilities.

Likewise, the mineral estate holder is unlikely seeking to forever condemn the right to extract hydrocarbons from all of the previously produced subsurface formations. Technology may evolve in the future that enables reservoirs to return to an economic viability for extraction.

All to point out, compensating a well operator who adopts a well bore for the carbon credits generated from abating hydrocarbon leaks through plugging the adopted well is nuanced, particularly given the complexity of interests between the surface and mineral estates.

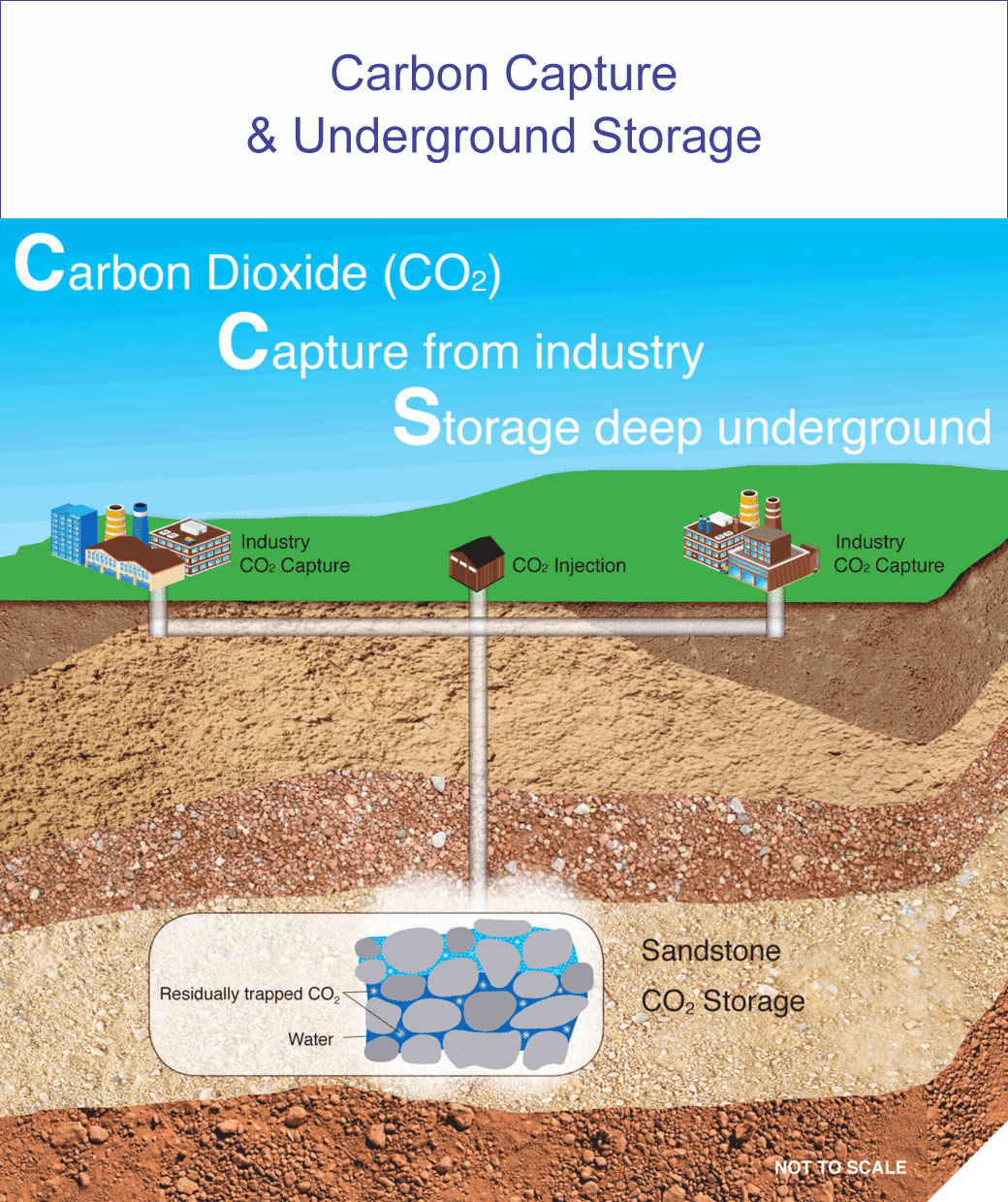

Increasingly, the desire for industry to eliminate carbon dioxide emissions through carbon capture and underground storage ("CCS") creates complexities as well.

Some of the best geological formations for CCS are near the "plays" and within the "basins" where hydrocarbons were historically produced. Therefore, if there is a viable subsurface formation for CCS that is shallower than an inactive or depleted oil and/or gas field, then the need increases to plug and abandon inactive wells. In this manner, the chance for carbon dioxide in a CCS project to migrate and find a way to the atmosphere is diminished. Indeed, there are entire bodies of regulation surrounding the long-term liability of CCS projects, with some states (e.g., North Dakota) taking responsibility for carbon dioxide emissions after the completion of a CCS project.

Not every well is primed for plugging and abandoning ("P&A"), or retirement. Some wellbore owners or operators maintain marginal production rates to avoid the P&A responsibility altogether. Other operators keep inactive wells (those not in production) on their asset ledgers because there remain intervals (deeper or shallower) that are prospective for future hydrocarbon recovery and production. Some wellbores lack owners, or their prior operators are impossible to locate, leaving landowners and mineral lessors exposed to ongoing reclamation problems.

All to say, the motivation to P&A and retire a hydrocarbon well is a conundrum.

Insightful information on inactive well retirement as a critical topic can be found at the following links:

But how large a problem are we talking about?

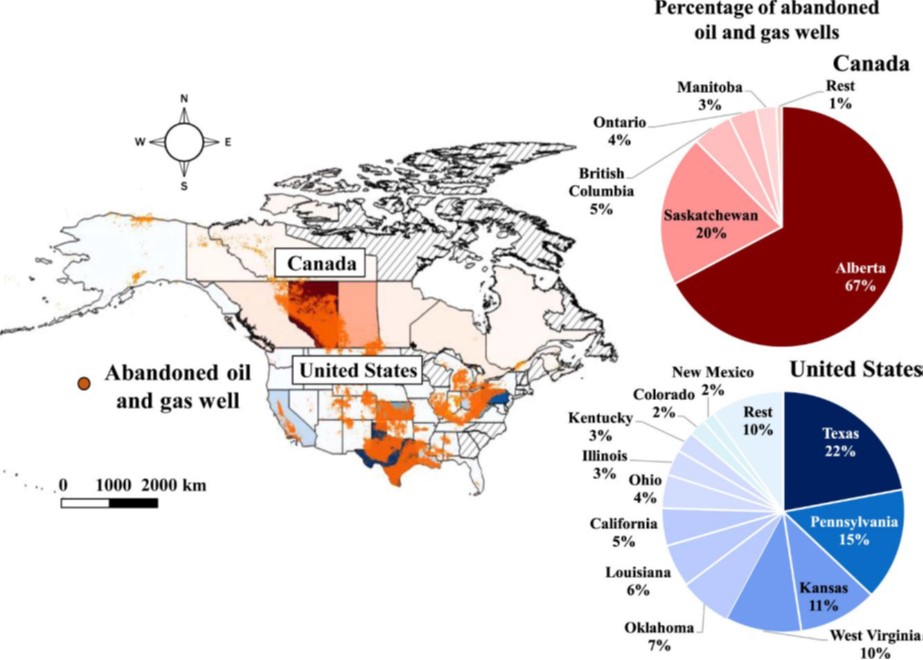

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) estimates there are 3.5 million abandoned oil and natural gas wells. Approximately 39% of these are plugged, leaving 2.1 million unplugged abandoned whether orphaned or inactive wells.[2] As of 2019, the EPA estimated 7.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide were being emitted of methane with a confidence interval of 1.1 to 20.8 million metric tons.[3][4]

The distribution of these estimated abandoned wells is below:

The US’ General Accountability Office estimates costs to properly plug a well on federal lands, where not as many wells have been drilled as on private property, can run anywhere from $20,000 to $145,000. Carbon Tracker Initiative utilizes a “flat rate” of $30,000, based on two sources which place average costs between $20,000-$40,000. The Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission meanwhile found that the average cost to plug a well in 2018 ranged from $3,700 to $97,626 – an average of $18,940. And environmental think tank Resources For the Future estimates a $24,000 per well price tag.[5]

Inclusive of the soft costs and adjoining surface reclamation activities, let’s assume an all-in cost of $65,000 for P&A. For 2.1 million wells, the aggregate cost is $138 billion!

[2] Orphan or inactive wells are defined differently in jurisdictions, sometimes as “shut-in”, “deserted”, “potentially deserted”, “temporarily abandoned”, “abandoned”, “potential orphan”, “unknown” (whether located or not), “orphan” or “orphan ready” and “forfeited”.

[3] Assessing Methane Emissions from Orphaned Wells to meet Reporting Requirements of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act: Federal Program Guidelines by US EPA, April 11, 2022. Section 40601 (Orphaned well site plugging, remediation, and restoration) of Title V (Methane Reduction Infrastructure) of the BIL provides the guidelines.

[4] As also evaluated by Blake Wright in “Hide and Seek: The Orphan Well Problem in America”, published in Journal of Petroleum Technology, August 2021.

[5] https://www.energyindepth.org/four-important-facts-to-keep-in-mind-on-latest-abandoned-wells-report/